(This e-mail from an American diving instructor working in Thailand was posted on PEACE, EARTH and JUSTICE (PEJ) News. See foot of article for subscription link.)

Sitting around, day after Christmas, just staring at the TV, some movie we've seen before. Mid-morning, post-breakfast stupor controlling Karin and me. The power flickers and we moan. We'll have to get up and do something? Then we hear some yelling outside.

I look out the front door, still puffed up with pride about our new house, just 400 feet back from the beach. People are running up our street yelling. It looks like a fire at the large two story resort that effectively blocks our view of the beach. Smoke and dust coming up and all these people.

Then a small line of really brown water comes rolling towards us. That's weird. But I reckon it must be some strange full moon high tide. So we go upstairs so we don't get wet. I look out the window and try and take some pictures. There is a quiet rumble to it, like those white noise generators that are supposed to help you sleep. The water is getting higher and higher and then it destroys our friends cement bungalow! Then our front door caves in, and then water is coming up the stairs! HOLY SHIT. This was the last point my brain worked for a long time.

We try and throw a mattress out the window to float on, but the water is rising too fast, and out the window we climb. It's all going so fast. It's faster than conscious thought and by the time we are on our second story roof, the water is coming out the window. We jump.

Karin doesn't jump at the same time or did I jump too early? We're separated. I scream her name, but the crashing roiling water mutes me. I can't hear her. I scream and scream until I get hit by something and pulled under. I can't swim to the top, I pull myself through trash and wood to the surface and off I go.

Ahead are trees wrapped in flotsam and as I look a Thai guy is struggling to get free of it, as I pass by at 30 MPH I realize he is impaled on a piece of wood and can't even scream.

My brain shut down when Karin disappeared, and now all I can do is survive. Something triggers and I swim. I swim to avoid the trees which will trap me, possibly kill me. It seems that I am atop the crest of the tsunami, which is less like a wave than a flood.

From on high I can see the water hit buildings, then rise, then watch the buildings collapse into piles of concrete and rebar. I swim to avoid these. Left and right I paddle, looking ahead the whole time trying to figure the hazards. None of this is conscious, this isn't me thinking it out, it's some recessed part of the brain coming out and taking control.

I was busy seeing the weird things, like massive diesel trucks being rolled end over end. Or the car launched through the 2nd storey wall of a former luggage shop. Or the person high up in a standing tree in a lurid orange thong. Or the older foreigner that got stuck in the wood and steel wrapped around a tree, and then his body torn off while his head remained. I couldn't scream.

I was pulled under, my pants caught on something, I decided that this was neither the place nor time for me to die, and ripped my pants off. I surfaced into a hunk of wood which cut my forehead. A 5 gallon water bottle sped by, and I wrapped myself around it like a horny German Shepard on a Chihuahua. I was passing people with bleeding faces and caked in refuse. Some people reached out to me, and I back, but the water was too fast and erratic. Some people screamed for help and I told them to swim. Some people just stared with empty eyes, watching what happened, but seeing nothing. Some were just floating bodies.

At some point, I passed a guy, cut on his cheek, holding onto big piece of foam. We just made eye contact and shrugged apathetically at each other. Then I turned ahead to watch fate. When I looked back he was gone.

Trees were pulled down, and their flotsam added to the flow. I was hit by a refrigerator and pushed towards a building that was collapsing. I swam and swam and swam and swam and still was pushed right towards a huge clump of jagged sticks and metal. I was pulled under, kicked towards the mass, cut my feet and kicked again. I popped up on the other side, spun around and pulled under again.

Down there, I knew it was not the time, and I pulled my way up through the floating rubbish of my former town. I pulled and pulled and my lungs ached for air. I flashed on Star Wars, the trash compactor scene, and had some big grin in the back of head as I popped up. Sucking shitty water and air deep in my lungs.

This went on for seeming weeks. Time simply left the area alone. I grabbed the edge of a mattress and floated. Breathing, just breathing. Awareness brought back by the sound and look of a water fall. Trying to push up onto the mattress more and more, and it took my weight less and less. Tumbling over the edge, sucked under again, and out I shot, swirled into a coconut grove, where the water seemed to have stopped. There was even a dyke like wall around the grove.

The water spun and churned, but went no where, and got no higher. It wasn't swimming, or climbing, but something in between. I made my way to the land. Every step had to be careful with broken glass everywhere, and sheet metal poking out. It was a long slow struggle.

The low rumble had stopped, and now is the occasional creak of wood on wood and metal scraping. Moans came across the new brown lake. A small boy was in a tree crying, asking for his parents in Norwegian.

I climbed up onto the dyke and looked around. I screamed out for Karin, only getting responses in Thai. I stood there, panting, trying to find a thought, anything. As I came back to earth I needed to pee. The first thing I did after surviving the tsunami was piss! Along limps an older Thai guy, finds me, naked atop a dyke amid the destruction, covered in mud and filth, pissing. He didn't even smile, nor did I.

I spent the next minutes running from high point to high point screaming out for Karin. If I made it, she could too. There was no response from her. I found plenty of other people, and helped who I could, but always looking across this vast area of new lakes for her head.

Through the trees was a PT boat, a large steel police cruiser. The boat and I had been brought more than a kilometer (2/3 mile) inland.

I was standing near a tree, hoping for a clue, anything to say she was out there somewhere. A small boy in a tree whimpered, and I pulled him down. We went inland. There were houses, still standing, a whole neighborhood atop a rise that was untouched. Just feet away were cars wrapped around trees. I handed them the boy.

I had finished my medic training exactly one month before, so I went to work. Pulling people out of mud, from under houses. One car, upright against the trunk of a tree still had the driver. He was dead. It went on. Before this I had only seen a dead body once or twice. That was remedied very quickly. I pulled people out of the water, only to have them choke and die right there. I would take someone's pulse, scream for help, then find that they had died before we could do anything. It was beyond any nightmare or fear I have ever had.

An older Thai woman came up to me with a pair of shorts and averted eyes. She was ashamed that I was totally naked. I smirked and slipped them on. She smiled and scurried away. Was it the bright white ass or the fear shriveled ***** that had embarrassed her?

Roaming the former streets looking for foreigners to send to the higher ground, a place where we could all meet and tend to wounds. After an hour the Thais came screaming out of the mud saying there was another wave coming, and flying into the hills. We were left alone. Those that could walk did, the rest were carried. We made a new base, higher and safer. And the same thing happened again. And again.

Eventually we ended up in the jungle at a park, where there was water and high ground. It was messy. Eventually there were about 300 foreigners, about 120 of whom were injured pretty severely with broken limbs and ribs, near-drownings, everyone had gashes of some kind, severed fingers or toes and shock everywhere.

There was no medicine, no tools, no scissors, no bandages. Nothing but well water (of questionable cleanliness) and some sticks and clothes. I tried to find anyone medically trained. It was only the diving instructors who all had basic first aid. So we cleaned with the water, we broke sticks and set bones and talked people into a relatively calm place. If someone was severely cut, we used their own clothing to mend the wounds. It was a horror story. The floor was covered in blood, people were moaning, or vomiting or asking us to help them. And more arrived with every new wave of cars and trucks fleeing the "next wave".

After hours of this, we got news of helicopters evacuating the injured. So everyone rushed towards the trucks. I had to scream and push and pull people out of the way. The ones who needed the evac the most were the ones who couldn't get to the trucks. After twenty minutes of sorting through the priorities, and feeling like we had a handle on it, someone brought me to a girl who was bleeding severely out of her thigh and was in shock. No one had brought her to our little clinic area, they had left her in the back of the truck.

Finally, after a few helicopters had pulled out the worst, I headed back down. Through rubber tree plantations, and coconut groves we drove. It seemed quiet and relaxed. At the last corner it was devastation. The road was clear and dry up to a certain point and then it was a horizon of rubble. I shuddered.

Someone on a scooter came up and asked for a doctor. Everyone looked at me! I jumped on and they took me up roads I never knew existed, and over bridges that were barely standing until I was brought to five foreigners in the middle of nowhere. One of them was a good friend and diving instructor. It was the first person I had seen that I knew. It was a total joy. He was banged up pretty bad, but he got out and sent off to the hospital. Then the Thais came roaring up the hill, saying there was another wave. We had to carry four more people with broken bones (including a broken hip) up a hill. There was no wave. There never was.

I stumbled back down, wandering through the town looking for people to help. I found only bodies. I found one with a tattoo like Karin's on a scooter under some rubble. I pulled her out, and it was a Thai woman. Still griping her scooter, mouth agape.

Eventually I made my way back to the dive shop I worked at. We had always whinged about how it was too far off the main road, but it survived. It was a center for the survivors. I walked up to find friends alive and things clean and organized.

I had been able to keep on, doing what I could to help people, to close out my mind to what was around me and look only at what I was doing, to not see the dead people, to not worry about where Karin was. I had held together so well.

When I found out Karin was alive it all fell apart. I could smell the destruction, the horror I had just walked through, just lived through, that she had lived through. My body shouted out all the bruises and cuts I had ignored. It all struck me and threw me to the ground. It was too much. I could no longer accept this.

We hugged and ate and slept. My feet were cut up, I had small cuts all over my body, and a sinus infection from all the bad water. Karin had gotten hold of a coconut tree, wrapped herself around it and never let go. She had a few bruises and small cuts and a black eye. I was ecstatic to see her like that. First time I've been happy to see a woman with a black eye.

Most of the rest of our friends had come through. They had set up first aid stations and help stations, organized food and created a center for people to meet. The diving community came together and became our support, our medical care, our food - they did everything they could to help and then some.

(snip)

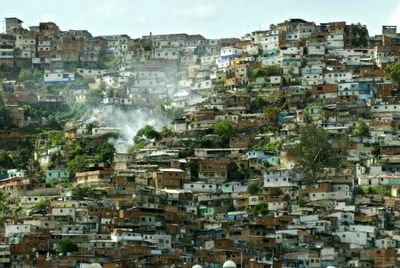

The next day I went back to where my house had been and surveyed the damage. One bungalow nearby had been lifted up and dropped on top of another. The whole beach was visible, meaning all of the two or three story hotels that had lined it were gone. There was a jet ski just near our house. The bottom floor of our house was gone, the upper floor was missing a couple of walls. The only thing left, was a plastic Jesus doll I had bought as a joke. So I was left with nothing in the world except my own plastic Jesus.

The level of destruction is virtually impossible to describe. On our beach we had approx. 2500 hotel rooms. It looked to me, that maybe 50 could still be called hotel rooms. The week between Christmas and New Year's is the busiest of the week. Without warning, without an evacuation plan the survival rates were minimal. The wave at our house was about 7 meters high (20 feet) and in some places it was 10 meters (30 feet) high. It wiped out the third floor of most resorts. The number of dead is astronomical, several thousand on my beach alone. By the second day you could smell it, and in the short walk to my former house, we passed about 10 bodies just strewn about.

Our final glance of the town was a cattle truck stacked full of wrapped up corpses. We wanted to go home.

In Bangkok most people got help pretty quick. The Swedes, Germans and English had charted flights for their citizens to get home. The Thai government gave free hotel rooms to survivors and there were lists of places to get food.

EXCEPT the Americans. I went in to find out what help I could get - I was able to get a replacement passport, a toothbrush and a paperback book. They said it was not their policy to arrange flights home. I was cut up, still covered in a pretty good layer of mud, I had no home, no money, no clothing (except some borrowed off Keith) nothing at all, and they could do nothing to help.

They did offer to let me borrow money, but they would have to find three people in America who would vouch for me, and that process should take less than a week. In the mean time I was fucked. I was destitute and rejected by the embassy. Karin was with me (she's Swedish) and said that I could still try and emigrate to Sweden. I was VERY tempted.

In these last days, watching politicians go on about helping and giving aide, but they won't even take care of their own citizens? I am very, very angry. All the other nations of the world were taking care of their own citizens! Eventually I got a flight home with JAL (that would be JAPAN airlines) not even an American company, but a JAPANESE company helped me get home.

I am still listed as neither found nor alive. Before I left I had spoken to the embassy twice on the phone, giving my name so I would be listed as alive so my family would not worry. I went to the embassy twice, once to get a passport to replace the one lost in the tsunami, and they never listed me as alive or found. I flew out of the country using said passport and am still not found. I went to the hospital three times, and, as of yesterday I am now listed as injured (having been in the states three days already). My family is now waiting to see how long it will take before they are notified about my status. So am I.

It does raise a good question - if I am missing or dead, do I have to pay taxes?

While spiteful about the embassy, I am grateful to be alive, and that those I care about are still alive. I still look around and am in awe at what just happened. I really feel like someone has slipped me some roofies and I woke up in America.

Note:

This account was received by email. References that identify the writer were removed - Rick Barnes, contributing editor PEJ News

To subscribe to PEJ News service and receive specific news feeds click

here