Regimental officers near Balaklava, ca.1855.

Causes of the war

In 1853 there was another religious riot in Jerusalem. This time it was between a crowd of Orthodox Christians and Catholics, and the dispute arose over control of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Several broken heads and deaths ensued.

The French Emperor (Napoleon III) demanded that France should be given protection of the Holy Places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The Russian Emperor (Nicholas I) demanded the same privilege for Russia, in addition to a protectorate over the estimated 12 million Orthodox Christians residing within Ottoman territories. The enfeebled Ottoman Empire, which controlled Palestine at the time, tried to make peace with both sides by offering secret (and conflicting) promises. They even sent a set of keys to the French, ostensibly those of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, although it was shortly discovered that they would not fit the door. Exasperated, but hardly in a position to offend either power, the Turks just hoped the problem would go away.

Well, it didn’t.

Other factors also came into play. Napoleon III was still smarting from a snub he had received from the Russian czar upon his accession to the French throne in 1852. The usual polite greeting among fellow monarchs was “Monsieur mon frere”, but Nicholas, no doubt remembering Napoleon’s infamous uncle and regarding the new self-styled emperor as an upstart, chose to use the greeting “Monsieur mon ami”. Within such small distinctions lie the seeds of war – one should never underestimate the vanity of kings.

Unlike his uncle, Napoleon III had been working hard to build up an alliance with England. If he went to war with Russia, he wanted England to come in at his side.

The British had their own problems with the Russians. Russian expansion into Central Asia seemed to threaten the borders of British India and already a Cold War of sorts had begun in Afghanistan, which was to gain momentum in the second half of the 19th century and become known as “The Great Game”. Equally important, from the British point of view, was to keep the Russian fleet bottled up in the Black Sea and prevent its gaining access to the Mediterranean through the Turkish-controlled Bosporus and Dardanelles.

The war might still have been avoided through a series of meetings and conferences if the Turks hadn’t surprised everyone by declaring war on Russia. They were immediately defeated by the Russian fleet at a great sea battle off Sinope. This enraged public opinion in France and England and a form of war fever took hold, encouraged by the popular press. The British and French expeditionary forces set sail for the Black Sea.

Early manouevres

The first port of call for the allies was Varna, near the mouth of the Danube in modern Rumania (at the time it was Austrian territory). The Russians had occupied Moldova and Wallachia in northern Rumania, but by the time the allies had arrived they had withdrawn their troops.

Now the French and British allies were faced with the problem of what to do next.

Obviously, they couldn’t pack up and go home after all the trouble and expense of equipping and shipping out 60,000 troops. Once you deploy an army (as we have learned from the Presidents Bush, father and son) you simply have to use it. After a period of dithering, it was finally decided to attack the port of Sevastopol, a large Russian naval base located at the southwestern end of the Crimean peninsula. It was considered a good idea to give a bloody nose to the Russian Navy, plus it was the only feasible target within range.

Map of the Crimea, showing major battles

The allied armies landed at Eupatoria, already suffering from illness and a scandalous shortage of basic supplies, and began to make their way south towards Sevastopol. A Russian force lined up on the heights south of the Alma river and a major battle was fought in which the allies were victorious after a series of uphill assaults on the Russian positions. They continued their march southwards, skirting well-defended Sevastopol, and establishing a base at Balaklava. A reinforced Russian Army moved down in force on their (inland) flank, which gave rise to the Battle of Balaklava and the magnificent (but foolish) charge of the Light Brigade.

The Charge of the Light Brigade

Cannon to the right of them,

Cannon to the left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well.

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

--Alfred, Lord Tennyson

It is difficult to judge this event as anything less than an act of blind folly. The charge had no effect on the course of battle on the day in question (October 25, 1855), nor on the war in general – apart from sadly reducing the British cavalry force. It was an aberration and seen as such by the Russian enemy ('Were they drunk?') as well as by their French allies ('C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre.'). How did it happen?

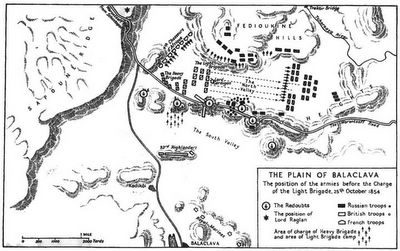

If you look at the map below, you can get an idea of what went wrong. Lord Raglan, the British Commander-in-Chief, had taken up position on an elevated spur of the Sapoune Heights (top left of map). His commander of cavalry, Lord Lucan, was at a lower elevation at the head of the North Valley and had a restricted view of the Causeway Heights and the Russian activity there which could be clearly seen by Raglan. The commander of the Light Brigade was Lord Cardigan, Lucan’s brother-in-law, stationed at the head of his troops in the North Valley. Cardigan was an irascible, cantankerous, but undeniably courageous commander. He and Lucan detested each other and were not on speaking terms. You can almost anticipate a disaster in the making.

Plan of the Battlefield (Click to Enlarge)

Raglan spotted Russian cavalry on the Causeway Heights, preparing to make off with captured British guns. He sent his "galloper" Captain Lew Nolan down to Lucan with vague orders to attack the guns. Lucan could not see the Russians on the Causeway Heights from his position, but could hardly credit that Raglan wanted him to attack the Russian batteries at the eastern end of the North Valley. This narrative begins after Raglan has sent the order to Lord Lucan.

------------------------------------------------

(Source: Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan, (Longmans, 1961. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr. Hibbert. Alvin Wee of the University Scholar's Programme, created the electronic text using OmniPage Pro OCR software, and created the HTML version. -- Marjie Bloy Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore.)

General Airey's A.D.C., Captain Lewis Edward Nolan, was a remarkable young man. His Irish father was in the British Consular service, his mother was Italian. He was extremely intelligent, goodlooking and excitable. He had written books on cavalry tactics and was considered by his fellow-officers as something of a prig. 'He writes books,' Lord George Paget said with some distaste, 'and was a great man in his own estimation and had already been talking very loud against the cavalry.' His contempt for both Lucan and Cardigan, but particularly Lucan, was violently and frequently expressed. He was, however, a superbly skilful horseman and it was because of this that Lord Raglan had chosen him rather than a more respectful officer to take the order to Lord Lucan six hundred feet below. A.D.C.s with previous orders had taken their horses carefully down, picking their way cautiously. Nolan went diving down the hill by the straightest and quickest route.

He galloped up to Lord Lucan and handed him the order. Lucan read it slowly with that infuriating care which drove more patient men than Nolan to scarcely controllable irritation. He read it, in fact, as he himself later confessed, 'with much consideration -- perhaps consternation would be the better word -- at once seeing its impracticability for any useful purpose whatever'. He urged 'the uselessness of such an attack and the danger attending it'.

'Lord Raglan's orders are,' Captain Nolan said, already mad with anger, 'that the cavalry should attack immediately.'

'Attack, sir! Attack what? What guns, sir? Where and what to do?'

'There, my Lord!' Nolan flung out his arm in a gesture more of rage than of indication. 'There is your enemy! There are your guns!' And leaving Lord Lucan as muddled as before, he trotted away to ask Captain Morris if he might charge with the 17th Lancers.

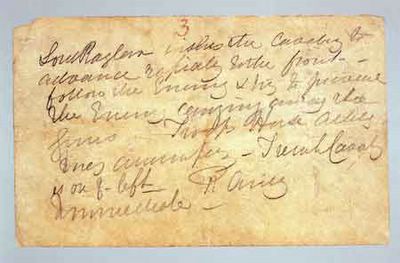

The order, written by General Airey and approved by Raglan, read as follows:Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front, follow the enemy & try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop Horse Artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediate. R Airey.

The trouble was that Lord Lucan had no idea what he was intended to do. He could not, on the plain, see nearly as far as Lord Raglan could on the hills above him. He could not see any redoubts. And he could not see any guns being carried away. Since the battle had begun he had taken no steps to find out what was happening beyond the mounds and hillocks and ridges which cut off his view of the ground that had fallen into the hands of the enemy. The only guns in sight were at the far end of the North Valley, where a mass of Russian cavalry was also stationed. Those must presumably be the ones Lord Raglan meant. Certainly Nolan's impertinent and flamboyant gesture had seemed to point at them. His mind now made up, Lord Lucan trotted over to Cardigan and passed on the Commander-in-Chief's order. Coldly polite, Lord Cardigan dropped his sword in salute.

Certainly, Sir,' he said in his loud but husky voice. 'But allow me to point out to you that the Russians have a battery in the valley in our front, and batteries and riflemen on each flank.'

I know it," replied Lucan. 'But Lord Raglan will have it. We have no choice but to obey.'

Cardigan saluted again, turned his horse, murmuring loudly to himself as he did so, 'Well, here goes the last of the Brudenells!', and he rode up to Lord George Paget. On the way he passed some men of the 8th Hussars who were smoking pipes. Their colonel angrily told them to put them out as they were 'disgracing his regiment by smoking in the presence of the enemy'. Paget himself was smoking a 'remarkably good' cigar and was embarrassed by Colonel Shewell's comment and then annoyed with Cardigan, who, after telling him to take command of the second line, added, 'and I expect your best support -- mind, your best support', repeating the last sentence 'more than once'.

'Of course, my Lord. You shall have my best support,' Paget replied, obviously nettled. He decided to keep his cigar.

Cardigan galloped back to the front of the brigade and drew it up in two lines. The 13th Light Dragoons were placed on the right of the front line, the 17th Lancers in the centre, the 11th Hussars on the left but slightly behind the regiments to the right of them. The 4th Light Dragoons and the 8th Hussars formed the second line. At the last moment Lucan, without consulting Cardigan, told Colonel Douglas to withdraw the 11th Hussars, Cardigan's regiment, from the first line and to take up a position in support of it.

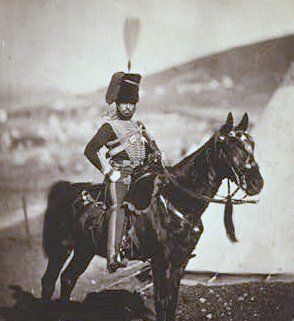

Officer of 11th Hussars ('Cherrypickers')

Cardigan himself rode forward to sit for a moment quite still and bolt upright in his saddle well in front not only of the first line but also of his staff. The spectators on the hills above excitedly leaned forward to watch what Camille Rousset afterwards referred to with cruel aptness as 'ce terrible et sanglant steeple-chase". They could see quite clearly the two white legs of Cardigan's chestnut charger.

They had, indeed, a magnificent view. They were on the Sapouné Ridge, which at this point overlooks the valley from its western end and falls down to the plain in a succession of grass-covered steps. On these steps those with no duties to perform sat in comfort and safety to watch the battle. Below them stretched the long and narrow North Valley; on their right the Causeway Heights; on their left the Fedioukine Hills. In front of them at the end of the valley, and facing the Light Brigade immediately below them, were the squadrons of Russian cavalry which had retreated over the Causeway Heights from the Heavy Brigade. Twelve guns had been unlimbered in front of them; three fresh squadrons of Lancers stood on each of their flanks; along the Fedioukine Heights were four additional squadrons of cavalry, eight battalions of infantry and fourteen guns. Opposite them, across the valley on the Causeway Heights, were the eleven battalions that had stormed upon the Turks and were now being gently prodded by Cathcart, and with them were a further thirty-two guns. Only a madman, as Lucan afterwards said, would expect men to charge into that open, mile-long jaw.

'The Brigade will advance,' Lord Cardigan said in a strangely quiet voice.

Lord Raglan and his staff did not immediately realise that anything had gone wrong. The direction of the advance was perhaps a little inclined to the left but not yet alarmingly so, and soon no doubt when the pace quickened the Light Brigade would swing to the right on to the Causeway Heights. This undoubtedly was what the Russians were expecting, for as the cavalry came slowly but determinedly towards them they withdrew from all but one of the captured redoubts and formed up in squares near the crest of the ridge. Here was Sir George Cathcart's opportunity, and some of his staff anxiously waited for him to take quick advantage of it. His division was still halted in the position it had taken up an hour or so previously, but he refused to move it, even though the redoubts he had been ordered to recapture were now no longer occupied. A staff officer urged him to advance. He said no, his mind was quite made up on the matter, and he would write to Lord Raglan.

For the first fifty yards the Light Brigade advanced at a steady trot. The guns were silent. Lord Cardigan in his splendid blue and cherry-coloured uniform with its pelisse of gold-trimmed fur swinging gently on his stiffly thin shoulders looked, as Lord Raglan afterwards said of him, as brave and proud as a lion. He never glanced over his shoulder, but kept his eyes on the guns in his front.

Suddenly the beautiful precision and symmetry of the advancing line was broken. Inexcusably galloping in front of the commander came that 'impertinent devil' Nolan. He was waving his sword above his head and shouting for all he was worth. He turned round in his saddle and seemed to be trying to warn the infuriated Lord Cardigan and the first line of his men that they were going the wrong way. But no one heard what words he was shouting, for now the Russians had opened fire and his voice was drowned by the boom and crash of their guns. A splinter from one of the first shells fired flew into Nolan's heart. The hand that had been so frantically waving his sword remained rigidly above his head, and his knees, as if even in death they could not forget the habits of a lifetime, still gripped the flanks of his horse. The horse turned round and, as his rider's sword slipped from the still raised hand, he galloped furiously back with his terrifying burden, which suddenly gave forth a cry so inhuman and piercingly grotesque that one who heard it described it as 'the shriek of a corpse'.

The pace began to quicken, and there could be no doubt now that most of these seven hundred horsemen were riding to their death. From three sides the round shot flew into the ranks and the shells burst between them, opening gaps which closed with so calm and unhurried a determination that men and women watched from the safety of the hills with tears streaming down their cheeks, and General Bosquet murmured, unconsciously delivering himself of a protest against such courage which was to be remembered for ever, 'C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre.' 'The tears ran down my cheeks,' General Buller's A.D.C. wrote, 'and the din of musketry pouring in their murderous fire on the brave gallant fellows rang in my ears.' 'Pauvre garçon!' said an old French general standing at his side, trying to comfort him, patting him on the shoulder. 'je suis vieux, j'ai vu des batailles, mais ceci est trop.'

Cardigan was still in front. An excited officer of the 17th Lancers rode up alongside him, and Cardigan held out his sword across his breast. 'Steady! Steady! the 17th Lancers,' Cardigan shouted above the roar of the guns.

Behind him could be heard the fragmented shouts of squadron commanders -- 'Close to your centre! "Do look to your dressing on the left!' 'Keep back, Johnson, back!' But more frequently than any other order -- 'Close in! Close in! Close in to the centre!' For men and horses were falling now in appalling numbers, and with every fifty yards the charging lines became narrower, more ragged, split and uneven, more confused. Wounded men stumbled back through the muddle of bleeding horses and their dead and dying friends. Terrified riderless horses thundered out of the smoke.

Seeing the Light Cavalry massacred in front of him, Lord Lucan turned to Lord William Paulet and said to him, 'They have sacrificed the Light Brigade, they shall not have the Heavy, if I can help it.' And he ordered the halt to be sounded, withdrawing the brigade to a position where he might be able to prevent the light cavalry being pursued on its return. Wounded in his leg, he had shown complete indifference under fire and earned the grudging admission of one of his most violent critics that 'Yes, he is brave, damn him.' It took courage of another sort to withdraw the Heavy Brigade at such a time and give his enemies further opportunity to misunderstand his reason for doing so.

The charge viewed from the Fedioukine Heights, with the Russian guns at the far left.

The Light Brigade was almost on the guns now. The officers had lost control of their men, who rushed on furiously, forcing Cardigan to increase his pace. Still so angry with Nolan that the only other thing he could think of was what it would be like to be cut in half by a cannon-ball, he picked out the smoke-filled space between the red flashes of two guns and rode straight for it. He was less than a hundred yards from the guns when all twelve of them simultaneously exploded in his face, rocking the earth and filling the air with thick smoke and flying metal. The Russian gunners had fired their last salvo before crawling under the guns. Cardigan was almost blown off his horse, but steadied himself and charged on into the battery at a speed, so he calculated with careful concern for accuracy, of seventeen miles an hour.

Only fifty men of the front line remained alive to follow him. But in they rushed, slashing at several brave Russian gunners who had not dived after their comrades under the guns but were pulling at the wheels in their efforts to drag them away. About eighty yards behind the guns were ranged the unmoving ranks of Russian cavalry. Cardigan looked at them with distaste. They all appeared to be gnashing their teeth. He took this to be a sign of greed at the sight of the rich fur and gold lace of his uniform. But other men had noticed before these 'numberless cages of teeth' in the pale, wide faces, and it was believed to signify not greed, nor even ferocity, but annoyance and impatience due to a thwarted wish to charge.

As Cardigan looked at them disdainfully, one of their officers, Prince Radzivill, looked back and remembered having met him at a party in London. He ordered some Cossacks to capture him alive. The Cossacks came forward, encircled him, and prodded him with their lances, cutting his leg. Cardigan glared scornfully at their wretched-looking nags, keeping his sword at the slope, as he considered it 'no part of a general's duty to fight the enemy among private soldiers', and then galloped away. He left his private soldiers to continue the fight while he trotted back up the valley to lodge a complaint about the infamous conduct of Captain Nolan.

Behind him the struggle continued unabated. Officers and men hacked at the Russian gunners, who hunched their heads between their shoulders as they tried to drag off their guns; while beyond the guns Captain Morris with what remained of the 17th Lancers charged at a mass of Russian cavalry and drove them back in disorder. He pursued them for some way until an enormous number of Cossacks forced his men back again.

Another body of Cossacks rode down on the men still fighting in the battery. Colonel Mayow, the Brigade Major, led the men out and drove the Russians off, as Lord George Paget galloped up and charged into the battery with the second line. The 4th Light Dragoons fell upon the gunners with a frightening savagery and massacred them with the ferocious excitement of Samurai. One British officer, maddened by the smell and sight of blood, clawed frenziedly at them with his bare hands, another swung his sword in the air screaming hysterically.

When all the Russian gunners were dead, the Dragoons charged on towards the cavalry beyond. But as they galloped through the still thick smoke, they ran into the 11th Hussars retreating before a vastly superior force of Russian lancers.

'Halt, boys!' Lord George shouted. 'Halt front. If you don't halt front, my boys, we're done.'

And so the two regiments, numbering between them less than forty men, stood at bay to face the advancing enemy. Suddenly a man shouted, 'They are attacking us, my Lord, in our rear.' It was true. Their retreat was cut off.

Lord George turned to Major Low. 'We are in a desperate scrape. What the devil shall we do? Where is Lord Cardigan?

But Lord Cardigan had trotted away, and there was only one thing that could be done.

'You must go about,' he called to the men, 'and do the best you can.'

The men rode hard and straight up the valley at the Russian lancers formed up across their line of retreat as fast as their 'poor tired horses would carry' them. The Russian lancers backed away as if they were preparing to fall on the flank of the retreating horsemen when they galloped past. But they did not do so. Restrained perhaps by that curiously indecisive leadership which was becoming a feature of Russian cavalry tactics, the lancers allowed Lord George's men to graze past them, half-heartedly pushing at them with their lances. Or perhaps it was that they were moved to compassion by the sight of these tattered remains of the most splendid-looking cavalry in the world.

For the men of the Light Brigade presented a pitiable sight. Their gorgeous uniforms were torn and smeared with blood, their horses as damp and bedraggled as water-rats. And they were the fortunate ones. Others went past on foot, alone or in pairs or dragging loved horses limping and bleeding to death behind them.

The ground was 'strewn with the dead and dying'. Horses in every position of agony struggled to get up, then floundered back again on their mutilated riders.

Even now the guns still fired at them. But only from the Causeway Heights. On the Fedioukine Hills the Russian artillery had been driven from their positions by a spectacular charge of the 4th Chasseurs d'Afrique, who had shown what brave horsemen can do when well directed and skilfully led.

The leader of the Light Brigade was already home. He, at least, felt clear of blame for the unskilful manner in which the brigade had been directed. 'It is a mad-brained trick,' he said to a group of survivors. 'But it is no fault of mine.'

He rode up to Lord Raglan to offer the same excuse.

'What did you mean, sir?' Raglan asked him, more angry than his staff had ever seen him before, shaking his head from side to side, the stump of his arm jumping convulsively in its empty sleeve. 'What do you mean by attacking a battery in front, contrary to all the usages of warfare and the customs of the service?'

Lord Raglan (left) with French and Turkish commanders.

'My Lord,' Cardigan said, confident of his blamelessness, 'I hope you will not blame me, for I received the order to attack from my superior officer in front of the troops.'

It was, after all, a soldier's complete indemnification. Lord Cardigan rode back to his yacht with a clear conscience. And when his anger had cooled Lord Raglan had to admit that the brigade commander was not to blame. He had 'acted throughout', he wrote in a letter typical of many generous comments on Cardigan's part in the disaster, 'with the greatest steadiness and gallantry, as well as perseverance'.

With Lucan, Lord Raglan was not so forgiving. Soon after his conversation with Cardigan, who had naturally put the entire blame on his brother-in-law, Raglan said to Lucan sadly, 'You have lost the Light Brigade.'

Lucan vehemently denied it. He had, he said, merely carried out an order given to him both in writing and verbally by an A.D.C. from Headquarters. Lord Raglan, according to Lucan, now made a curious reply.

'Lord Lucan,' he said, 'You were a lieutenant-general and should, therefore, have exercised your discretion and, not approving the charge, should not have caused it to be made.'

****

Under flags of truce the dead and wounded were brought back from the now silent valley, while patrols trotted slowly across the space separating the two armies. Horses streaming with blood and unable to get to their feet bit at the short grass with froth-covered teeth. And every now and then men winced at the sharp, melancholy sound of the farriers' pistols. Nearly five hundred horses were lost.

Of the 673 men who had charged down the valley less than two hundred had returned. The Russians, as well as the allies, were deeply moved by such heroism. General Liprandi could not at first believe that the English cavalry had not all been drunk. 'You are noble fellows,' he told a group of prisoners, 'and I am sincerely sorry for you.'

The allies had need of sympathy. The engagement could not, whatever feats of courage had been displayed, be considered a victory. Balaclava admittedly had not been taken, but the Russian armies now straddled the Causeway Heights. And the road, which ran along the top of them and which might have saved the army from some of the horrors of the coming winter, was lost.

---------------------------------------------------

Next, a fictional account of the same events from "Flashman at the Charge"

(Copyright resides with the author, George MacDonald Fraser, whose indulgence I seek for this lengthy - and lightly edited - extract, secure in the conviction that readers coming upon a typical chunk of the Flashman Papers for the first time will immediately rush out and buy as many books in the series as possible. This narrative begins just before Raglan composes his order.)

Directly beneath where I stood, at the near end of the valley, our cavalry had taken up station just north of the Causeway, the Heavies slightly nearer the Sapoune and to the right, the Lights just ahead of them and slightly left. They looked as though you could have lobbed a stone into the middle of them – I could easily make out Cardigan, threading his way behind the ranks of the 17th, and Lucan with his gallopers, and old Scarlett, with his bright scarf thrown over one shoulder of his coat – they were all sitting out there waiting, tiny figures in blue and scarlet and green, with here and there a plumed hat, and an occasional bandage … The distant pipe of voices drifted up from the plain, and from the far end of the Causeway a popping of musketry; for the rest of it was all calm and still, and it was this tranquility that was driving Lew to a frenzy, the blood-thirsty young imbecile.

Well, thinks I, there they all are, doing nothing and taking no harm; let ‘em be, and let’s go home. For it was plain to see the Ruskis were going to make no advance up the valley towards the Sapoune; they’d had their fill for the day, and were content to hold the far end of the valley and the heights either side. But Raglan and Airey were forever turning their glasses on the Causeway, at the Russian artillery and infantry moving among the redoubts they’d captured from the Turks; I gathered both our infantry and cavalry down in the plain should have been moving to push them out, but nothing was happening, and Raglan was getting the frets.

‘Why does not Lord Lucan move?’ I heard him say once, and again: ‘He has the order; what delays him now?’ Knowing Look-on, I could guess he was huffing and puffing and laying the blame on someone else. Raglan kept sending gallopers down – Lew among them – to tell Lucan, and the infantry commanders, to get on with it, but they seemed maddeningly obtuse about his orders, and wanted to wait for our infantry to come up, and it was this delay that was fretting Raglan and sending Lew half-crazy.

And just at that moment someone sang out: ‘My lord! See there – the guns are moving! The guns in the second redoubt – the Cossacks are getting them out!’

Sure enough, there were Russian horsemen limbering up away down the Causeway crest, tugging at a little toy cannon in the captured Turkish emplacement. They had tackles on it, and were obviously intent on carrying it off to the main Russian army. Raglan stared at it through his glass, his face working.

Lew was writhing with impatience in his saddle. ‘Oh, Christ!’ he moaned softly. ‘Send in Cardigan, man – never mind the bloody infantry. Send in the Lights!’

Good idea, thinks I – let Jim the Bear skirmish into the redoubts, and get a Cossack lance where it’ll do most good. So you may say it was out of pure malice towards Cardigan that I piped up – taking care that my back was to Raglan, but talking loud enough for him to hear:

‘There goes our record – Wellington never lost a gun, you know.’

I’ve heard since, from a galloper who was at Raglan’s side, that it was those words, invoking the comparison with his God Wellington, that stung him into action – that he started like a man shot, that his face worked, and he jerked at his bridle convulsively. Maybe he’d have made up his mind without my help – but I’ll be honest and say that I doubt it. As it was he went pale and then red, and snapped out:

‘Airey – another message to Lord Lucan! We can delay no longer – he must move without the infantry. Tell him – ah, he is to advance the cavalry rapidly to the front, to prevent the enemy carrying off the guns – ah, to follow the enemy and prevent them. Yes. Yes. He may take troop horse artillery, at his discretion. There – that will do. You have it, Airey? Read it back, if you please.’

‘Send it immediately,’ Raglan was telling Airey. ‘Oh, and notify Lord Lucan that there are French cavalry on his left. Surely that should suffice.’ And he opened his glass again, looking down at the Causeway Heights. ‘Send the fastest galloper.’

I had a moment’s apprehension at that – having started the ball, I’d no wish to be involved – but Raglan added: ‘Where is Nolan? – yes, Nolan,’ and Lew, beside himself with excitement, wheeled his horse beside Airey, grabbed at the paper, tucked it in his gauntlet, smacked down his forage cap, threw Raglan the fastest of salutes, and would have been off like a shot, but Raglan stayed him, repeating that the message was of the utmost importance, that it was to be delivered with all haste to Lucan personally, and that it was vital to act at once, before the Ruskis could make off with our guns. All unnecessary repetition of course, and Lew was in a fever, going pink with impatience.

Capt. Lewis Nolan, 15th Hussars (contemporary watercolour)

‘Away, then!’ cries Raglan at last, and Lew was over the brow in a twinkling, with a flurry of dust – showy devil – and Raglan shouting after him: ‘At once, Nolan – tell Lord Lucan at once, you understand.’

‘Flashman,’ says Raglan, ‘Nolan must make it clear to Lord Lucan – he is to behave defensively, and attempt nothing against his better judgment. Do you understand me?’

Well, I understood the words, but what the hell Lucan was expected to make of them, I couldn’t see. Told to advance, to attack the enemy, and yet to act defensively. But it was nothing to me; I repeated the order, word for word, making sure Airey could hear me, and then went over the bluff after Lew.

I was the better horseman. He wasn’t twenty yards out on the level when I touched the bottom and went after him like a bolt, yelling to him to hold on. He heard me, and reined up, cursing, and demanding to know what was the matter. ‘On with you!’ cries I, as I came alongside, and as we galloped I shouted my message.

‘Defensive?’ cries Lew. ‘Defensive be damned! He must have said offensive – how the hell can he attack defensively? And this order says nothin’ about Lucan’s better judgment. For one thing, he’s got no more better judgment than Mulligan’s bull pup!’

‘Well, that’s what Raglan said!’ I shouted. ‘You’re bound to deliver it.’

‘Ah, damn them all, what a set of old women!’ He dug in his spurs, head down, shouting across to me as we raced towards the rear squadrons of the Heavies. ‘They don’t know their minds from one minute to the next. I tell ye, Flash, that ould ninny Raglan will hinder the cavalry at all costs – an’ Lucan’s not a whit better. What do they think horse-soldiers are for? Well, Lucan shall have his order, and be damned to them!’

I eased up as we shot through the ranks of the Greys, letting him go ahead; he went streaking through the Heavies, and across the intervening space towards the Lights. I’d no wish to be dragged into the discussion that would inevitably ensue with Lucan, who had to have every order explained to him three times at least. But I supposed I ought to be on hand, so I cantered easily up to the 4th Lights, and there was George Paget again, wanting to know what was up.

‘You’re advancing shortly,’ says I, and ‘Damned high time, too,’ says he. ‘Got a cheroot, Flash? – I haven’t a weed to my name.’ I gave him one, and he squinted at me. ‘You’re looking peaky,’ says he. ‘Anything wrong? ‘Bowels,’ says I. ‘Damn all Russian champagne. Where’s Lord Look-on?’

And then I heard Lucan’s voice, clear as a bugle. ‘Guns, sir? What guns, may I ask? I can see no guns.’

He was looking up the valley, his hand shading his eyes, and when I looked, by God: you couldn’t see the redoubt where the Ruskis had been limbering up to haul the guns away – just the long slope of Causeway Heights, and the Russian infantry uncomfortably close.

‘Where, sir?’ cries Lucan. ‘What guns do you mean?’

I could see Lew’s face working; he was scarlet with fury, and his hand was shaking as he came up by Lucan’s shoulder, pointing along the line of the Causeway.

‘There, my lord – there, you see, are the guns! There’s your enemy!’

He brayed it out, as though he was addressing a dirty trooper, and Lucan stiffened as though he’d been hit. He looked as though he would lose his temper, but then he commanded himself, and Lew wheeled abruptly away and cantered off, making straight for me where I was sitting to the right of the 17th. He was shaking with passion, and as he drew abreast of me he rasped out:

‘The bloody fool! Does he want to sit on his great fat arse all day and every day?’

And with that he went over to Tubby Morris, and I thought, well, that’s that – now for the Sapoune, home and beauty, and let ‘em chase to their hearts content down here. And I was just wheeling my horse, when from behind me I heard Lucan’s voice.

‘Colonel Flashman!’ He was sitting with Cardigan, before the 13th Lights. ‘Come over here, if you please!’

Now what, thinks I, and my belly gave a great windy twinge as I trotted over towards them. Lucan was snapping at him impatiently, as I drew alongside:

‘I know, I know, but there it is. Lord Raglan’s order is quite positive and we must obey it.’

‘Oh, vewy well,’ says Cardigan, damned ill-humoured; his voice was a mere croak, no doubt with his roupy chest, or overboozing on his yacht. He flicked a glance at me, and looked away, sniffing; Lucan addressed me.

‘You will accompany Lord Cardigan,’ says he. ‘In the event that communication is needed, he must have a galloper.’

I stared horrified, hardly taking in Cardigan’s comment: ‘I envisage no necessity for Colonel Fwashman’s pwesence, or for communication with your lordship.’

‘Indeed, sir,’ says I, ‘Lord Raglan will need me … I dare not wait any longer … with your lordship’s permission, I –‘

‘You will do as I say!’ barks Lucan. ‘Upon my word, I have never met such insolence from mere gallopers before this day! First Nolan, and now you! Do as you are told, sir, and let us have none of this shirking!’

And with that he wheeled away, leaving me terrified, enraged, and baffled. What could I do? I couldn’t disobey – it just wasn’t possible. He had said I must ride with Cardigan, to those damned redoubts, chasing Raglan’s bloody guns – my God, after what I had been through already! In an instant, by pure chance, I’d been snatched from security and thrust into the melting-pot again – it wouldn’t do. I turned to Cardigan – the last man I’d have appealed to, in any circumstances, except an extremity like this.

‘My lord,’ says I. ‘This is preposterous – unreasonable! Lord Raglan will need me! Will you speak to his lordship – he must be made to see –‘

‘If there is one thing,’ says Cardigan, in that croaking drawl, ‘of which I am tolewably certain in this uncertain world, it is the total impossibiwity of making my Word Wucan see anything at all. He makes it cwear, furthermore, that there is no discussion of his orders.’ He looked me up and down. ‘You heard him, sir. Take station behind me, and to my weft. Bewieve me, I do not welcome your pwesence here any more than you do yourself.’

At that moment, up came George Paget, my cheroot clamped between his teeth.

‘We are to advance, Lord George,’ says Cardigan. ‘I shall need close support, do you hear? – your vewy best support, Lord George. Haw-haw. You understand me?’

George took the cheroot from his mouth, looked at it, stuck it back, and then said, very stiff: ‘As always, my lord, you shall have my support.’

James Brudenell, 7th Lord Cardigan

‘Haw-haw. Vewy well,’ says Cardigan, and they turned aside, leaving me stricken, and nicely hoist with my own petard, you’ll agree. Why hadn’t I kept my mouth shut in Raglan’s presence? I could have been safe and comfy up on the Sapoune – but no, I’d had to try to vent my spite, to get Cardigan in the way of a bullet, and the result was I would be facing the bullets alongside him. Oh, a skirmish round gun redoubts is a small enough thing by military standards – unless you happen to be taking part in it, and I reckoned I’d used up two of my nine lives today already. To make matters worse, my stomach was beginning to churn and heave most horribly again; I sat there, with my back to the Light Brigade, nursing it miserably, while behind me the orders rattled out, and the squadrons reformed; I took a glance round and saw the 17th were now directly behind me, two little clumps of lances, with the Cherrypickers in behind. And here came Cardigan, trotting out in front, glancing back at the silent squadrons.

He paused, facing them, and there was no sound now but the restless thump of hooves, and the creak and jingle of the gear. All was still, five regiments of cavalry, looking down the valley, with Flashy out in front, wishing he were dead and suddenly aware that dreadful things were happening under his belt. I moved, gasping gently to myself, stirring on my saddle, and suddenly, without the slightest volition on my part, there was the most crashing discharge of wind, like the report of a mortar. My horse started; Cardigan jumped in the saddle, glaring at me, and from the ranks of the 17th a voice muttered: ‘Christ, as if Russian artillery wasn’t bad enough!’ Someone giggled, and another voice said: ‘We’ve ‘ad Whistlin’ Dick – now we got Trumpetin’ Harry an’ all!’

‘Silence!’ cries Cardigan, looking like thunder, and the murmur in the ranks died away. And then, God help me, in spite of my straining efforts to contain myself, there was another fearful bang beneath me, echoing off the saddle, and I thought Cardigan would explode with fury. I could not merely sit there. ‘I beg your pardon, my lord,’ says I, ‘I am not well –‘

‘Be silent!’ snaps he, and he must have been in a highly nervous condition himself, otherwise he would never have added, in a hoarse whisper: ‘Can you not contain yourself, you disgusting fellow?’

‘My lord,’ whispers I, ‘I cannot help it –. it is the feverish wind, you see –‘ and I interrupted myself yet again, thunderously. He let out a fearful oath, under his breath, and wheeled his charger, his hand raised; he croaked out: ‘Bwigade will advance – first squadron, 17th – walk-march – twot!’ and behind us the squadrons stirred and moved forward, seven hundred cavalry, one of them palsied with fear but in spite of that feeling a mighty relief internally – it was what I had needed all day, of course, like these sheep that stuff themselves on some windy weed, and have to be pierced to get them right again.

And that is how it began. Ahead of me I could see the short turf of the valley turning to plough, and beyond that the haze at the valley end, a mile and more away, and only a few hundred yards off, on either side, the enclosing slopes, with the small figures of Russian infantry clearly visible. You could even see their artillerymen wheeling the guns round, and scurrying among the limbers – we were well within range, but they were watching, waiting to see what we would do next. I forced myself to look straight ahead down the valley; there were guns there in plenty, and squadrons of Cossacks flanking them; their lance points and sabers caught the sun and threw it back in a thousand sudden gleams of light. Would they try a charge when we wheeled right towards the redoubts? Would Cardigan deploy the 4th Lights? Would he put the 17th forward as a screen when we made our flank movement? If I stuck close by him, would I be all right? Oh, God, how had I landed in this fix again – three times in a day? It wasn’t fair – it was unnatural, and then my innards spoke again, resoundingly, and perhaps the Russian gunners heard it, for far down the Causeway on the right a plume of smoke blossomed out as though in reply, there was the crash of the discharge and the shot went screaming overhead, and then from all along the Causeway burst out a positive salvo of firing; there was an orange flash and a huge bang a hundred paces ahead, and a fount of earth was hurled up and came pattering down before us, while behind there was a crash of exploding shells, and a new barrage opening up from the hills on the left.

Suddenly it was, as Lord Tennyson tells us, like the very jaws of hell; I realized that, without noticing, I had started to canter, babbling gently to myself, and in front Cardigan was cantering too, but not as fast as I was (one celebrated account remarks that, ‘In his eagerness to be first at grips with the foe, Flashman was seen to forge ahead; ah, we can guess the fierce spirit that burned in that manly breast’ – I don’t know about that, but I’m here to inform you that it was nothing to the fierce spirit that burned in my manly bowels). There was a crash-crash-crash of flaming bursts across the front, and the scream of shell splinters whistling by; Cardigan shouted ‘Steady!’, but his own charger was pacing away now, and behind me the clatter and jingle was being drowned by the rising drum of hooves, from a slow canter to a fast one, and then to a slow gallop, and I tried to rein in that little mare, smothering my own panic, and snarling fiercely to myself: ‘Wheel, wheel, for God’s sake! Why doesn’t the stupid bastard wheel?’ For we were level with the first Russian redoubt; their guns were leveled straight at us, not four hundred yards away, the ground ahead was being torn up by shot, and then from behind me there was a frantic shout.

I turned in the saddle, and there was Nolan, his sabre out, charging across behind me, shouting hoarsely, ‘Wheel, my lord! Not that way! Wheel – to the redoubts!’ His voice was all but drowned in the tumult of explosion, and then he was streaking past Cardigan, reining his beast back on its haunches, his face livid as he turned to face the brigade. He flourished his saber, and shouted again, and a shell seemed to explode dead in front of Cardigan’s horse; for a moment I lost Nolan in the smoke, and then I saw him, face contorted in agony, his tunic torn open and gushing blood from shoulder to waist. He shrieked horribly, and his horse came bounding back towards us, swerving past Cardigan with Lew toppling forward on to the neck of his mount. As I stared back, horrified, I saw him careering into the gap between the Lancers and the 13th Light, and then they had swallowed him, and the squadrons came surging down towards me.

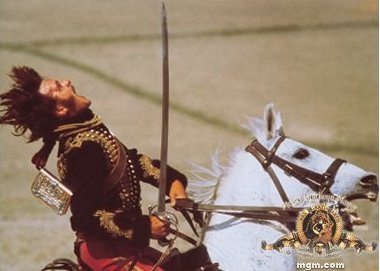

Nolan Cops It (David Hemmings in the 1968 film wearing the uniform of Cardigan's 11th Hussars, instead of the 15th, to which Nolan actually belonged)

I turned to look for Cardigan; he was thirty yards ahead, tugging like damnation to hold his charger in, with the shot crashing all about him. ‘Stop!’ I screamed. ‘Stop! For Christ’s sake, man, rein in!’ For now I saw what Lew had seen – the fool was never going to wheel, he was taking the Light Brigade straight into the heart of the Russian army, towards those massive batteries at the valley foot, that were already belching at us, while the cannon on either side were raking us from the flanks, trapping us in a terrible enfilade that must smash the whole command to pieces.

‘Stop, damn you!’ I yelled again, and was in the act of wheeling to shout at the squadrons behind when the earth seemed to open beneath me in a sheet of orange flame; I reeled in the saddle, deafened, the horse staggered, went down, and recovered, with myself clinging for dear life, and then I was grasping nothing but loose reins. The bridle was half gone, my brute had a livid gash spouting blood along her neck; she screamed and hurtled madly forward, and I seized the mane to prevent myself being thrown from the saddle.

Suddenly I was level with Cardigan; we bawled at each other, he waving his saber, and now there were blue tunics level with me, either side, and the lance points of the 17th were thrusting forward, with the men crouched low in the saddles. It was an inferno of bursting shell and whistling fragments, of orange flame and choking smoke; a trooper alongside me was plucked from his saddle as though by an invisible hand, and I found myself drenched in a shower of blood. My little mare went surging ahead, crazy with pain; we were outdistancing Cardigan now – and even in that hell of death and gunfire, I remember, my stomach was asserting itself again, and I rode yelling with panic and farting furiously at the same time. I couldn’t hold my horse at all; it was all I could do to stay aboard as we raced onwards, and as I stared wildly ahead I saw that we were a bare few hundred yards from the Russian batteriesThe great black muzzles were staring me in the face, smoke wreathing up around them, but even as I saw the flame belching from them I couldn’t hear the crash of their discharge – it was all lost in the fearful continuous reverberating cannonade that surrounded us. There was no stopping my mad career, and I found myself roaring pleas for mercy to the distant Russian gunners, crying stop, stop, for God’s sake, cease fire, damn you, and let me alone. I could see them plainly, crouching at their breeches, working furiously to reload and pour another torrent of death at us through the smoke; I raged and swore mindlessly at them, and dragged out my saber, thinking, by heaven, if you finish me I’ll do my damndest to take one of you with me, you filthy Russian scum. (‘And then,’ wrote that fatuous ass of a correspondent, ‘was seen with what nobility and power the gallant Flashman rode. Charging ahead even of his valiant chief, the death cry of the illustrious Nolan in his ears, his eyes flashing terribly as he swung the saber that had stemmed the horde at Jallalabad, he hurtled against the foe.’) Well, yes, you might put it that way, but my nobility and power was concentrated, in a moment of inspiration, in trying to swerve that maddened beast out of the fixed lines of the guns; I had just sense enough left for that. I tugged at the mane with my free hand, she swerved and stumbled, recovered, reared, and had me half out of the saddle; my innards were seized with a fresh spasm, and if I were a fanciful man I’d swear I blew myself back astride of her. The ground shook beneath us with another exploding shell, knocking us sideways; I clung on, sobbing, and as the smoke cleared Cardigan came thundering by, saber thrust out ahead of his charger’s ears, and I heard him hoarsely shouting:

‘Steady them! Hold them in! Cwose up and hold in!’

The Brigade crashes into the Russian gun batteries.

I tried to yell to him to halt, that he was going the wrong way, but my voice seemed to have gone. I turned in the saddle to shout or signal the men behind, and my God, what a sight it was! Half a dozen riderless horses at my very tail, crazy with fear, and behind them a score – God knows there didn’t seem to be any more – of the 17th Lancers, some with hats gone, some streaked with blood, strung out any old how, glaring like madmen and tearing along. Empty saddles, shattered squadrons, all order gone, men and beasts going down by the second, the ground furrowing and spouting earth even as you watched – and still they came on, the lances of the 17th, and behind the sabers of the 11th – just a fleeting instant’s thought I had, even in that inferno, remembering the brilliant Cherrypickers in splendid review, and there they were tearing forward like a horde of hell-bound specters.

-------------------------------------------------------

What happens next? Well, quite a lot happens next as any dedicated fan of the Flashman series has blithely come to expect. There is a new one coming out in April this year.

The conclusion of the war and its aftermath

In appalling conditions of fog and rain the allies defeated the Russians at the Battle of Inkerman on the eastern approaches to Sevastopol, and then laid siege to the city itself. The siege was prolonged due to bad weather and the suffering among the troops was made infinitely worse by the criminal neglect which had attended the support of the allied armies, in particular that of the British, since the very opening of the campaign. Cholera had decimated the army in Varna even before it had re-embarked for the Crimea. Food supplies were inadequate and medical attention was primitive, prompting a private citizen, Florence Nightingale, to fund and set up a hospital for evacuees at Scutari near Istanbul. Tents were in short supply and most of the army had to sleep in the open in freezing conditions, often clad in the rags that were all that remained of their original uniforms. Deaths resulting from disease and exposure were four times higher than battlefield casualties.

After a spirited defence of several months’ duration – a siege which produced its own heroes (scant attention is paid to the Russian side of this war) -- Sevastopol fell to the allies and the war was brought to a negotiated conclusion with little lasting advantage to the nominal winners.

Russia went to war with Turkey again in 1877, and the European Powers imposed a settlement (the 1878 Treaty of Berlin) which managed to put a lid on the vexatious Eastern Question (what to do with the crumbling Ottoman Empire?) for another 30 years.

In 1908 the Austrian Empire annexed Bosnia-Hercegovina in a rash moment of imperial overstretch and this brought it into contention with neighbouring Serbia. Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece allied against Turkey in 1912, and, having removed the last remnants of Turkish rule from the Balkans, fell out among themselves in 1913. Serbia gained an overall advantage from these Balkan Wars and the Austrians began to feel the need to teach these Slavic upstarts a lesson. The Serbs, as Orthodox Christians, enjoyed the support of Russia. On June 28, 1914 the heir to the Austrian throne, Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated by Serb nationalists while on an official visit to the Bosnian capital Sarajevo. The Austrians were determined to punish Serbia and called on Germany for help. The Serbs asked the Russians for support. Russia called in its alliance with France. The Germans had only one military plan for a two-front war, the Schlieffen Plan of 1909, which called for a massive invasion of France through neutral Belgium in the belief that the Russians would be unable to mobilize and deploy their forces before the campaign in France had been concluded. Unfortunately, Britain had better relations with France than with Germany (the Entente Cordiale) and had also a binding 1839 obligation to protect the neutrality of Belgium.

In this way, we ended up with the First World War (see Armistice Day article on this Blog) which created a political balance of forces in Europe and the World which persevered – roughly – until 1989-91. Then we had a new round of Balkan Wars.